Programme (re-)design

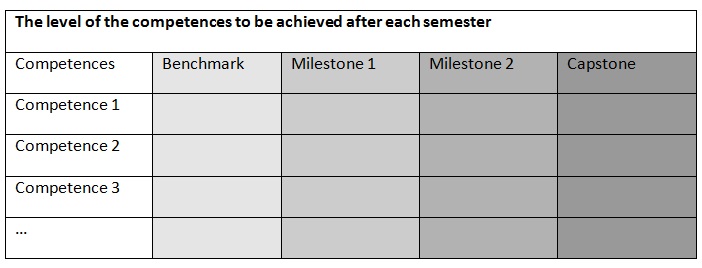

- 1. Formulation of the final qualifications (FQs) i.e. the ILOs at programme level

- 2. Formulation of the educational activities in a curriculum

- 3. Formulation of the assessment programme (also called assessment plan)

Step 1: Formulation of the final qualifications (FQs) i.e. the ILOs at programme level

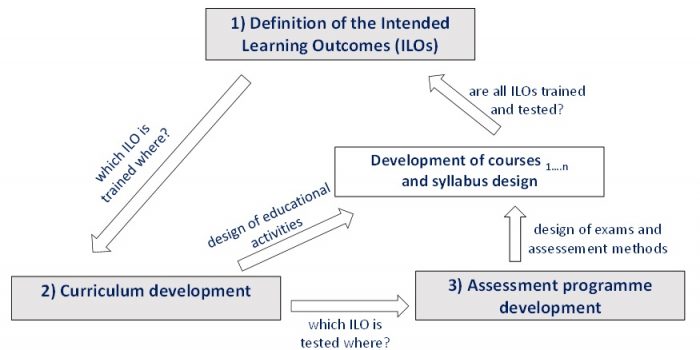

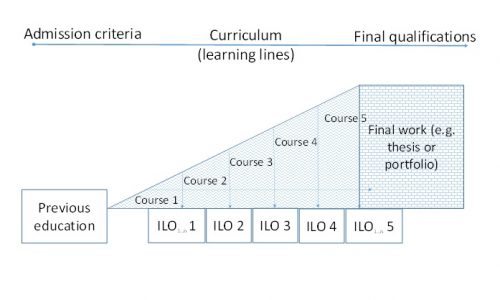

The definition of Final Qualifications (FQs) is based on the vision of the educational institution on the demand of the labour market for professionals with a particular expertise, the general economic and social context and also the expertise developed within the educational institution in terms of research and training capacities. Moreover, at this stage a decision needs to be taken as to the admission requirements and the entry level of the inflowing students (e.g. required prior qualifications and competences). These considerations (see Figure) typically are done within the curriculum development working groups (curriculum committee) and should fit the larger educational vision and portfolio of expertise within the faculties i.e. the Faculty and UM strategic vision and mission.

At this step the path through which the educational goals is charted, i.e., the FQs will be achieved. Essentially, this is a process of mapping out in the timespan of the educational programme (typically 3 years for a BA degree, 1 year for a regular MA degree and 2 years for a Research Master degree) the necessary teaching and learning activities and didactic choices. In practice one needs to define the learning trajectories (or learning lines/’leerlijnen’) and plot them across the educational units (courses of e.g., 4 or 8 weeks) as illustrated in the figure.

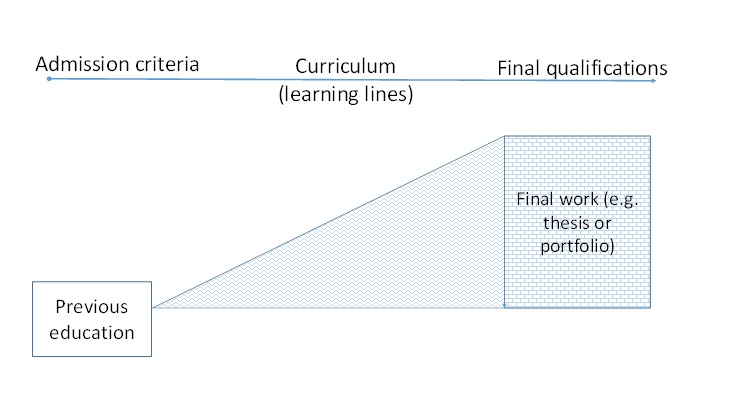

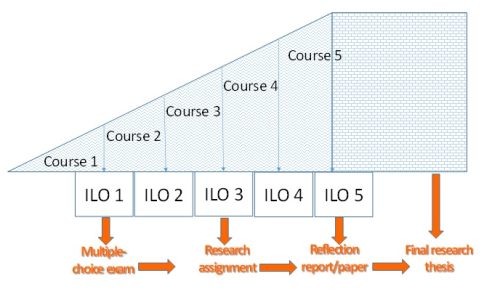

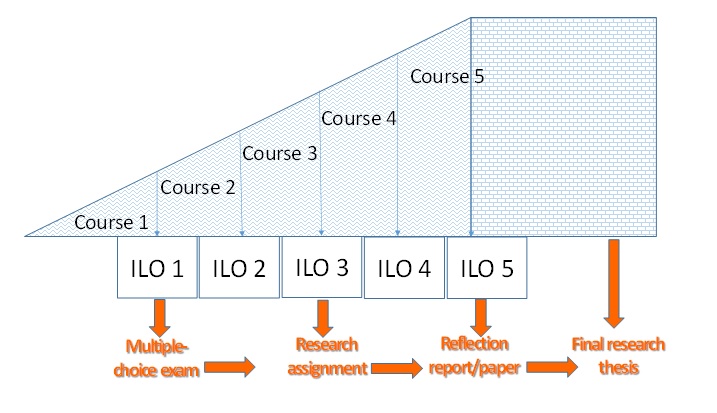

Here is the place to give meaning and shape to the PBL didactics within the educational programme, but also to consider whether all FQs can be reached solely based on the PBL method or other educational activities are necessary as well (e.g., training of research methods or particular professional skills typically are trained via workshops or simulations of the professional practice). Moreover, this is the step where the process of acquisition of the competence is defined as well as the expected end-level according to the adopted taxonomy of learning outcomes. The decision about the level of the learning outcome (e.g. understanding, application, analysis, creation) usually narrows down the choice of assessment methods during the next step. the figure on the right displays the learning line “Statistical training” within a MA programme at FASoS, whereby the final qualification is defined at the highest (creation) level.

As the figure shows, the learning trajectory starts in course 1 with basic knowledge and understanding, as well as with application on an existing dataset. In course 3 the students are trained to design surveys and collect data (application skills). In course 5 they acquire the understanding how to process and analyse the collected survey data, and via the final work they are tested on the highest level (creation skills), namely to design a survey, collect data via questionnaires, process and analyse the data. In a similar way, all learning lines need to be designed and mapped out for each final qualification that is trained progressively in several courses of the programme.

At this step a decision is expected about the path through which the progressive achievement of the learning goals and of the FQs will be tracked and formally assessed. It is expected that this path assures sufficiently precise monitoring of the students’ learning curve toward the final qualifications. The set of exams and assessments should be valid, reliable and transparent (for a definition of these terms, see chapter 2.5). Moreover, it is expected that the assessment programme incorporates a variety of the assessment formats and ideally includes as many as feasible authentic for the profession deliverables.

The decision how to compose and organize the assessment programme heavily depends on the choices of learning outcomes (especially the expected end-level), as well as the didactic vision and capacity to grade of the staff members. For example, higher levels of learning outcomes involve a certain degree of socialization in the professional behaviour i.e. are trained longer and require more moments of formative assessment (which has a steering function). Moreover, they are tested via more complex deliverables such as research papers, professional reports, or ‘products/services’ which are characteristic to the job for which the educational programme prepares (e.g. advisory/consultancy report, design advice, medical/psychological examination, etc). Conversely, learning outcomes which do not involve that much analytical skills and only cognitive retention can easily be tested with multiple-choice exams. The figure below illustrates this point by displaying the assessment format choices related to the example above – the learning line “Statistical training” within a MA programme at FASoS. The final qualification is defined at the highest (creation) level, but prior to that the student undergoes a test of knowledge and application via a multiple-choice test in course 1. Then, in course 3, the student drafts a research assignment where the composition of the survey questionnaire is explained and justified (test at the level of Analysis). Consequently, a reflective report/paper is required in course 5 to test the capacity of the student to process the collected raw survey data (test at the level of Evaluation). Finally, the student drafts the final MA thesis, which includes all steps from operationalization of the variables, through the development of an own questionnaire, dataset, and the analysis thereof (this is the ultimate competence acquisition attainment defined at the level of Creation).

2.3 Programme (re-)design: practical instructions

The steps charted in the previous section, concern designing an educational programme from scratch. It is possible, however, to aim at aligning an existing programme to the CoAL principles. Under this scenario, while the steps are essentially the same, much more preparatory work needs to be done e.g. through the study of the current courses and their ILOs, adjustment of the FQs, a good overview of the existing learning trajectories, and/or inventory and development of missing learning trajectories. Moreover, the re-design operation is much more complex than the direct design because a management of change trajectory is necessary.

If the educational programme already exists, a potential revision will affect existing (entrenched) interests and stakes behind the current curriculum. These need to be taken into account, and carefully managed toward the new and desired version of the curriculum. But first of all, you need to gain support and cooperation of the stakeholders involved in the (re-)design.

How to re-design a programme and manage change

Constructive alignment requires a particular way of thinking about higher education. While its principles are quite simple, it is often not easy to achieve constructive alignment in an existing programme. Existing programmes often do not have the luxury of starting fresh. They already have a history and there might be entrenched interests of stakeholders. Change will only succeed if the key stakeholders understand the core ideas of CoAl and regard them as fair and useful. This means that achieving constructive alignment, and maintaining it in a curriculum, is a team effort. The process of redesign and implementation is thus as much a team building process (see Box 2.1) as an educational innovation/curriculum redesign process. This paragraph aims to provide some recommendations on how to start the constructive alignment process when redesigning a programme in such a way that it is not a chore, but a mind-set that motivates staff to guard and improve the quality of education as a team.

There is no prescribed best way to start the change process. You can find suitable instruments of change in sections concerning internal audits, staff development and external advisory board.

Recommendation 1: Start small, less is more

It is imperative to take it slow in the beginning: Firstly, because you need time and some experience to optimize the process to be able to convince others, and secondly, because ‘infecting the masses’ is a gradual process. First, you need some early adopters, who understand that at first things can be a bit messy, but are nevertheless enthusiastic and persevere. This ‘coalition of the willing’ will be your greatest asset. Their first experiences will give you the opportunity to share successful experiences and to be transparent about improvements you made to the system. After you have made it work in one or a small number of courses or programmes (e.g. one BSc and one MSc) you can gradually increase the number of programmes you include. Similarly, it might be wise to limit the number of ILOs.

A common mistake is the impression that course coordinators have to cover every objective in every course. Keep it lean, make sure there’s as little bureaucracy as you can afford, as this is often perceived as a sign of repression rather than an invitation for an open discussion. In this context, it might be recommendable to get the paperwork done by the educational policy advisors, and to let the coordinators just discuss openly, and agree on the big picture (main ILOs, teaching methods, assessment formats). In practice this will mean that the workshops are attended by educational advisors who after the workshop translate the discussion into tables, curriculum maps, etc. This will facilitate the coordinators, but will also get the right content on paper (because the educational advisors are experts in the formulation of ILOs and choice of TLAs/assessment methods).

Recommendation 2: Communication is crucial

People tend to be distrustful of new tasks and even more so when it comes with certain rules or a bit of bureaucracy. For this reason it is important to make sure your communication is not solely about what staff has to do (or else!), but about how this is beneficial for them:

- Teachers get the means to see whether their students are learning what they are supposed to be learning (validity).

- It makes courses and programmes more efficient because teachers can focus on teaching the topics and skills you (as a programme /course coordinator) think is important, while other course coordinators can address other topics/competences.

- The focus on intrinsic quality and organisation of goals, instruction and assessment means that quality of education is not solely defined by students’ perceptions from surveys.

- It is easier to explain the purpose of a constructively aligned course to students, which helps recruiting motivated students to join the course or programme.

- The courses remain up-to-date with regard to developments regarding the whole programme.

- The course/programme is safeguarding its fundamental principles and quality standards because the paperwork prepared in the process of implementation of the CoAl project can be reviewed by internal or external quality assurance committees in order to verify the quality of the educational process offered.

A personal approach usually works best: talk with people before you start sending emails which can be misinterpreted. Make sure the staff knows that whatever challenges you find along the way, you will solve them together.

Recommendation 3: Always keep the end-goal in mind

The reason for implementing CoAl is to improve or maintain the quality of education. All processes are subservient to this one goal. Also, the system(s) you implement to measure constructive alignment can never become more important than student learning. This is especially important because different education programmes can require a different approach. If something doesn’t work, change it.

Three scenarios in programme (re-)design

- Agree on who is going to coordinate the programme update.

- Evaluate/ make an inventory of the current situation: what is the current state of the programme regarding CoAl? And which changes are required or desired?

- Are programme ILOs still up-to-date?

- Are course ILOs well-formulated?

- Are course ILOs well aligned with the programme ILOs

- Is there a clear and good alignment between the course ILOs, teaching/learning methods and assessment methods?

- Plan how you will develop the adjustments. Try to integrate your planning in the existing structure of your faculty. Make sure that all relevant stakeholders are included. Create a timeline.

- Start working out your plan: implement and monitor.

Example of a minor update

The Bachelor Psychology is an existing programme at Maastricht University. From 2010 onwards a curriculum redesign was implemented. The programme ILOs, course structure and modules were defined. These programme ILOs reflect the international, European and national guidelines and the FPN emphasis on biological and cognitive psychology in a Problem Based Learning format. A curriculum map provides an overview of the linkage between the courses and the programme ILOs.

In 2016, FPN decided to evaluate whether the programme of the Bachelor Psychology is still up-to-date and constructively aligned. No large adjustments are expected.

Process

The programme coordinator coordinates this process, supported by the policy advisor education. Course coordinators are informed and involved: The programme coordinator informs the course coordinators regularly in the ‘curriculum year groups’ (in Dutch ‘curriculum jaargroepen’) meetings. The management staff is informed in the three-weekly meeting of the Education Management Team. Since the aim is to adjust the existing curriculum only where needed (no complete re-design, but minor changes), the starting point is the current curriculum. In a first step, the programme coordinator and policy advisor mapped out the content of the courses and the course ILOs based on the course books and tutor instructions. Course coordinators are subsequently asked to check these maps. Meanwhile, the programme ILOs were discussed in a meeting with the programme coordinator, policy advisor, EDLAB liaison/coordinator internationalisation and a senior lecturer who was involved in the former curriculum redesign.

Based on these opinions, the following points of attention are identified:

- 21st century skills: Throughout the curriculum three learning lines are present in the curriculum: 1) Statistics, 2) Research methodology, 3) Academic writing skills. A fourth line focusing on communication and visualisation skills is advisable. Some courses already use learning activities that focus on creating communication or visualisation skills. But these are not aligned. Besides, there is little focus on intercultural knowledge and skills. Depending on the new strategic programme, an increased focus on intercultural knowledge and skills (adjusting learning outcomes) might be desirable.

- Update of relevant frameworks: There are no recent changes in the requirements of the existing frameworks (Criteria set by the Dublin descriptors, Qualification Framework for the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), Criteria set by the National Qualifications Framework The Netherlands (NQFT), Europsy criteria set by the European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations (EFPA), Criteria set by the Dutch cluster of Psychology (in Dutch: ‘Kamer Psychologie’), Criteria set by the Dutch National Institute for Psychologists (NIP), Criteria set by the Dutch vLOGO regarding post-academic education (Gezondheidszorgpsycholoog, Klinisch psycholoog, Psychotherapeut)).

- UM and FPN strategic programme: Currently UM and FPN are working on a new strategic programme.

At course level, the following points of attention are identified:

- Each course has formulated objectives in terms of the content. But not all courses have ILOs specified according to the principles of constructive alignment.

- The translation from ILO to teaching/learning and assessment method is not described explicitly for most courses.

Timeline

The following timeline was set:

- June 2016: Evaluate the programme ILOs and make an inventory of the course ILOs and course topics, learning and assessment methods. The inventory of the courses is made by the Bachelor Programme Coordinator and Policy Advisor Education, and checked critically by the course coordinators.

- July-August 2016: Based on the current inventory of the courses, feedback from course coordinators and evaluation of the programme ILOs, required changes are identified (e.g. New aspects required in the curriculum? Gaps in the curriculum? Overemphasize on certain topics?)

- September –November 2016: Course coordinators will be involved to include the adjustments in the nominal plans for 2017/2018.

- November 2016 – February 2017: The adjustments suggested for the nominal plans 2017/2018 are discussed and set by the different committees involved.

- March 2017 onwards: The adjustments in the programme will be implemented in 2017/2018.

When considering the redesign of an entire educational programme, in principle all three edges of the CoAl triangle can function as a departure point, and can function as a trigger to the educational reform. In other words one could start by:

- Examining and updating the final qualifications and the learning outcomes of the courses.

- Examining and updating the educational activities i.e. the content of the study materials, lectures,

assignments and PBL-tasks. - Examining and updating the assessment programme i.e. the choice of assessment formats or final

work deliverables.

Each of these departure points or approaches provides advantages and disadvantages. In this book (and concretely in the FASoS example discussed below) we accord preference to departing from the final qualifications i.e. the ILOs at programme level, because the accreditation by the NVAO is done at the programme level.

Example complete re-design

FASoS: Re-Design MA programme “Globalisation and Development Studies”

Step 1: the final qualifications of the programme (FQs) were updated and reformulated following changed circumstances on the educational landscape of the Netherlands (appearance of competitors, new insights from research, changed socio-political context especially with regard to the study of migrant flows and re-conceptualization of the Global South vs Global North divide).

The leading questions at this step were: Are the FQs and the current learning trajectories up-to-date? What adjustments need to be performed?

These questions were answered based on input from the teaching team, but leading was the vision of the Director of Studies, the curriculum committee and the Faculty Board. This step of the process had as a final deliverable a revised list of final qualifications.

Step 2: the ILOs at course level were discussed in a meeting with the entire team of course coordinators, where the Director of Studies informed the team about the revised FQs. Each course coordinator was requested to reflect on the following questions (which are also the leading ones for this step of the process):

- Considering the newly formulated final qualifications of the programme: which ILOs of your course can remain the same, which need to be adjusted, and which need to be dropped?

- Considering the newly formulated final qualifications of the programme: look critically at the content of the study materials, lectures, assignments, PBL-tasks and other educational activities of your course: which can remain the same, which need to be adjusted, and which need to be dropped?

- Considering the newly formulated final qualifications of the programme: look critically at the assessment methods and formats of your course: which can remain the same, which need to be adjusted, and which need to be dropped?

The team received instructions on how to reformulate the ILOs for their course, namely that a good learning outcome has the following characteristics:

- has a clear and unambiguous content;

- contains an “active verb” i.e. a measurable action or cognitive performance that can be observed.

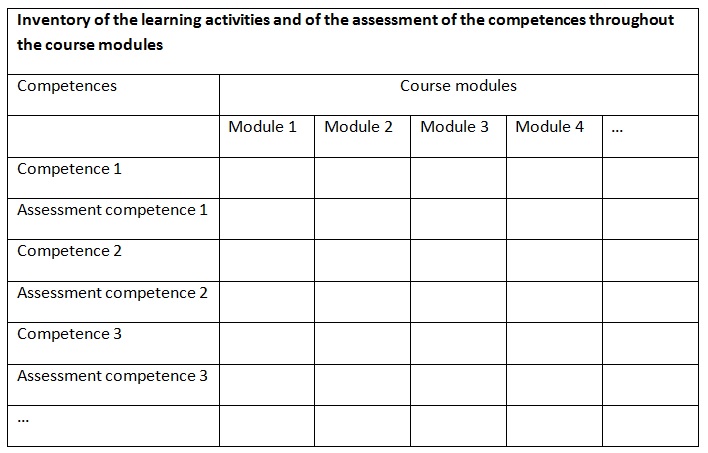

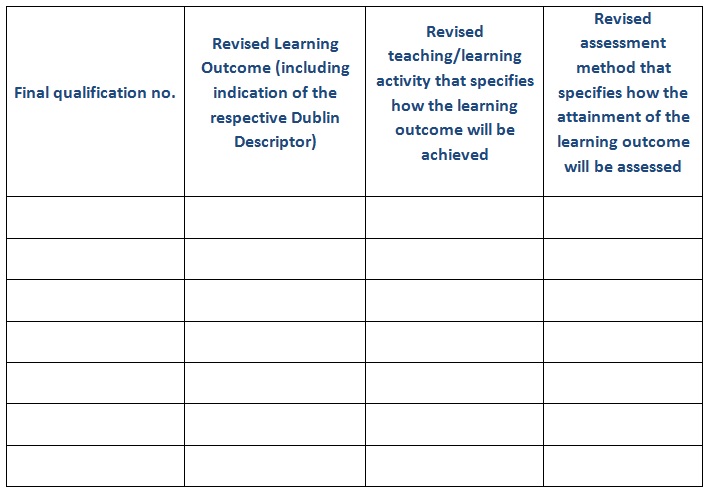

Each coordinator was requested to come up with a revised education dossier of their course, which in practice meant that they had to fill-in the following table:

To facilitate the coordinators in the process of revision each of them received:

- a list of active verbs following the taxonomy of Bloom (see Annex II, p. 85);

- a list of the Dublin-level descriptors of learning outcomes, which are nowadays standard requirement of the NVAO re-accreditation framework;

- stand-by consultation (upon request) with the educational expert of FASoS.

This step of the process had as a final deliverable a revised educational dossier for each course.

Step 3: revision and adjustment of the learning lines. Upon completion of the educational dossiers for every course, the educational advisor critically assessed the existing learning lines within the programme and re-drafted them. In practice this meant a revised version of the curriculum of educational activities. At this stage there was also an inventory made as to whether all final qualifications are ‘covered’ and adequately assessed. In practice this meant a revised version of the assessment programme (also often called assessment plan) of the programme.

The leading questions at this step were: In light of the introduced revisions of the FQs and the course educational dossiers, what adjustments need to be performed in the curriculum and in the assessment programme? How does the entire education plan of the programme need to be revised?

The work was done primarily by the educational expert of FASoS with occasional consultations with the course coordinators and the Director of Studies.

This step of the process had as final deliverables:

- a revised draft-curriculum with revised learning lines (including links to the final qualifications),

- a draft-assessment programme (including links to the final qualifications)

- recommendations for adjustment of the individual course books.

Step 4: the revised drafts of the curriculum of educational activities and the draft assessment programme were discussed in a meeting with the entire team of course coordinators, where the educational expert informed the team about the introduced revisions and their rationale.

The leading questions at this step were: Are the revised curriculum of educational activities and the revised assessment programme coherently adjusted? Are the introduced revisions acceptable to the entire team? Can all team-members work with the new version of the programme Education plan? Was the redesign process successful?

The entire team discussed the new outlook of the educational programme (i.e. the entire Education plan) and was invited to provide final comments and remarks. Wherever necessary, final corrections were introduced.

This final step of the process had as final deliverables:

- a revised draft-curriculum with revised learning lines (including links to the final qualifications),

- a draft-assessment programme (including links to the final qualifications)

- recommendations for adjustment of the individual coursebooks.

- Define your programme ILOs based on the aims of the new programme and the relevant frameworks;

- Define the structure of your programme, including the course ILOs, teaching activities and assessment methods;

- Align your programme and course ILOs.

Example IJRMWOP

The International Joint Research Master Work and Organisational Psychology (IJRMWOP) is a new two-year master under construction. It will be a joint Master of Maastricht University, the University of Valencia, and Leuphana University. At the moment of writing this example, the programme is in the process of the macro-efficiency check (‘macrodoelmatigheidstoets’) and the concrete structure of the programme is still under construction.

Aims of the programme

The programme aims to provide high quality research training in the domain of Work and Organisational (W&O) psychology, which implies that students are taught the state-of-the art theories and developments in W&O psychology, and provide knowledge and skills for a wide range of research techniques, including fundamental research but also research & development requirements.

Relevant frameworks

The programme will build on the reference curriculum model for academic education and training in W&O psychology that was developed by the European Network of Organizational Psychologists (ENOP) and is now widely accepted as the basis for curriculum development for W&O psychology in Europe.

Programme content has been determined after close scrutiny of various qualifications frameworks including the European Qualifications Framework for LifeLong Learning (level 7), the Tuning-Europsy reference points, the overarching Qualifications Framework of the European Higher Education Area, the reference model and minimal standards of the European Network of Organizational and Work Psychologists, the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology’s guidelines for education and training at the Master’s level in Industrial and Organizational psychology and the German qualification framework (Deutscher Qualifikations-rahmen) as well as recent debates on graduate training in the discipline.

Within the programme development, the term research is broadly defined to include basic research, applied research, evaluation research, R&D, translation -, and innovation research, and non-standard consultancy.

Final qualifications

The following core research competencies will be developed in the programme:

- Research design and implementation

- Development of research methods and tools, and interventions

- Data analysis

- Scientific writing

- Writing research proposals / fund raising

- Research dissemination and valorisation

- Innovation

In addition, the following enabling competencies will be developed:

- Communication (oral-, stakeholder-,…)

- Cross-cultural competence

- Team work

- Ethical competence

- Self-regulation and self-management, organisational citizenship behaviour, planning

Work process/stakeholders

The formulated competences resulted from a two-day brainstorm with a group of nine professors from all three universities. This group was also responsible for specifying aims and frameworks, and for the selection of course courses. Often, existing courses could be modified to fit into the new programme. One university (UM) was chosen to coordinate further development of the programme and supporting (e.g. accreditation) documents, which involved online fine-tuning and two subsequent face-to-face meetings with teachers and support staff. In addition, the coordinating university was responsible for setting up an initial consortium agreement and for writing an application for a macro-efficiency check, which the Dutch Ministry of Education requires in order to decide on funding a new programme. Consequently, there was a need to demonstrate that the programme met labour market and societal and/or scientific needs.

Structure of the programme

The programme will consist of course courses offered at the three Universities involved in this Master. The next step in designing the programme is to map out the competences that are developed and assessed in the different courses using the curriculum map below. For each semester, the level of competence to be achieved will be defined. If needed, the courses and corresponding ILOs will be adjusted.