Internal Quality Assurance

In order to assure that the achieved alignment at course and programme level is maintained and sustainably revised, a comprehensive quality assurance (QA) system needs to be in place.

The main actors of such a system are stipulated already in the Dutch Higher Education and Research Act (WHW):

- Programme Coordinators (also alled Programme Directors/Directors of Studies);

- Associate Dean of Education (portfolio-holder Education);

- Programme committees.

- Board of Examiners;

- Potentially a Test Committee (toetscommissie).

In addition, the educational institution typically organizes and maintains a support structure of educational databases, of educational policy advisors, educational administration, etc. All these actors come sequentially into play within the so-called quality assurance cycles and they use various instruments that verify and improve the educational quality.

It is beyond the remits of this website to address all such instruments and processes. Instead, in what follows the main actors, tools, and processes are presented that have direct bearing to the systematic maintenance of the CoAl principles within the educational practices. The tabs below outline the main actors and their typical competences, the informational infrastructure (database), and the instruments of internal quality assurance.

Who is responsible for embedding and maintaining the CoAl principles in the educational programme? Who is responsible for warranting them?

Constructive Alignment is a joint effort. Once embedded in the initial programme design, it needs to be maintained and warranted. This is a complex iterative – ideally yearly – exercise which involves various parties from the educational institution. The section below provides a brief overview of the main UM actors and their function:

- Programme Directors (also called Programme Coordinators / Directors of Studies): this is probably the most engaged person with CoAl in the educational programme. Based on the existing curriculum map/education plan the Director of Studies supports and manages the links between the intended learning outcomes (ILOs), the teaching methods, and the assessments of the whole programme. This is the linking pin between the strategic educational management: Faculty Board, External Quality Assurance institutions, the curriculum committee, and the “work-floor” i.e. the course coordinators, the examiners and the students.

- Course Coordinators (teachers): they have to implement in practice the coupling of the ILOs to teaching activities and to assessment formats. Moreover, they continuously maintain the balance of the CoAl triangle within the course, but also to reflect upon the position of their individual course in the context of the whole programme (relation to other courses and to the final qualifications/ ILOs). It is also advised to communicate this to students in the course book.

- Students: the student perspective on the achieved CoAl within the courses and the entire programme can be very insightful. This is why the students should be encouraged to submit evaluations and discuss the programme cohesion (via IWIO evaluations or student panel discussions).

- Educational policy advisors: continuously monitor that CoAl is observed in the creation and redesign of courses, and in revision of curricula. The educational policy advisors provide recommendations on how to implement and maintain CoAl on a course and programme level. Moreover, they draft the re-accreditation self-study reports and maintain the institutional database of education plans, curriculum maps, and other necessary CoAl documentation.

- Educational Programme Committee: this committee is charged with discussing the rationale of the programme and to evaluate its coherence. In its work the programme committee can use the CoAl as a guiding principle and as a point of departure to offer recommendations to change and to adjust educational processes, learning outcomes, didactic approaches, assessment formats, etc.

- Board of Examiners: this is one of the main actors when it comes to quality assurance of assessment practices. According to the WHW, this committee is expected to guarantee the quality of examinations within the institution, and to act as a warrant of the Faculty diploma certificates. It is therefore crucial to convince the BoE in its role of a watchdog to pursue and warrant the CoAl principles. Moreover, given the toolbox of instruments, which the BoE possesses with regard to the CoAl edge assessment – it can trigger change in the other 2 edges (ILOs and TLAs).

- Curriculum committee: this is a committee mainly charged with the curriculum (re-)design and therefore a potentially primary trigger of change when it comes to the principles of CoAl. Ideally, this committee was already led by CoAl in the initial stages of the curriculum design, but CoAl can be achieved also at a late stage. The curriculum committee could be a vital actor via its advices to the programme director and the Faculty Board.

- Faculty Board: this is a body for strategic management and steering, which is only indirectly involved in CoAl processes. Nevertheless, its support is crucial in order to launch the process (including financial back-up of the project) and to keep the momentum. Moreover, based on the monitoring of and the contacts with the external environment, the Faculty Board can provide input for CoAl by proposing new final qualifications or ILOs to enter the curricula of the educational institution.

One of the crucial questions when it comes to processes of QA is about the interaction and the division of responsibilities between the actors within the quality assurance cycle. It is advisable to agree upon and fix the interaction pattern that works for the faculty/educational unit in an Actor-Responsibility matrix, which specifies the tasks and remits of engagement per activity. The next tab provides a list of the typical activities related to safeguarding the CoAl at a course and programme level. Each educational programme is advised to hold a discussion and delineate the responsibilities per row from this table in order to assure smooth functioning of the quality assurance cycle related to the CoAl principles.

The focus of Constructive Alignment lies with the design of education. However, we know that education programmes are dynamic – keeping up with changing society, new scientific insights, and changes in staffing. In other words, there is a tension between the orderliness of design and the messiness of reality.

One familiar example is problem-based learning (PBL), where it is felt by many that current PBL-practices are not always in line with the original intentions. To manage this need for change in a structural manner, the Maastricht University School of Business and Economics has developed an ‘Assurance of Learning’ (AoL) system. This AoL system distinguishes from other evaluation methods itself by its focus on education itself instead of surveys (student perceptions) and its cyclical nature.

A core feature of AoL is the triennial internal audit where a panel of peers evaluates whether and how the ILOs of the programme are achieved. In doing so, the audit panel reviews samples of student products (e.g. exams, papers) and other information from education (e.g. grade metrics, course manual). The audit is not intended to judge the performance of academic staff, rather the audit triggers a series of conversations about the curriculum: firstly, among the members of the audit panel, secondly between the audit panel and the programme coordinator and the programme director, and thirdly between the programme coordinator and the course coordinators. The value of these conversations should not be underestimated, sincea great deal

of informal learning takes place that reinforces the mind-set required for CoAl on programme level – like a refresher course in fundamentals of CoAl. The conversations result in a set of agreements which are documented and feed back in the annual educational renewal cycle. Because an audit takes place every three years, the education team is motivated to implement improvements in the next academic year.

- 1. Informal learning: audits maintain awareness of CoAl and diffuse best-practices in the organisation

- 2. Continuous improvement: audits lead to concrete improvements

- 3. Coherence: the programme as a whole is the main unit of analysis, not the courses

- 4. Outsider perspective: Bringing in fresh ideas and a critical eye

- 5. Team building: it signals that education is a common good

What kind of internal instruments and processes facilitate the implementation and warranting of the CoAl principles?

In order to facilitate the communication between all the responsible actors outlined and to ensure the continuity of the CoAl principles, it is recommended to work with a well-documented education plan. An education plan focuses on how an academic programme is contributing to the learning, growth, and development of students as a group. A good education plan reflects all programme choices regarding the FQs, the measureable student learning outcomes per course, the teaching and learning activities, and the assessment methods. Thus, an education plan is the material evidence of CoAl both at course and at programme level.

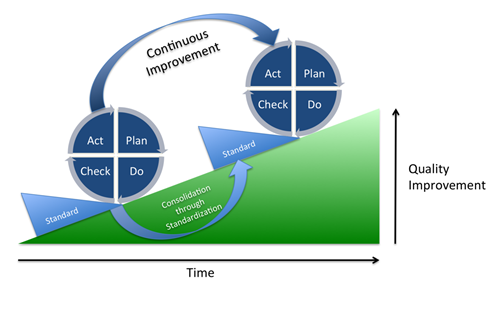

The education plan (EP) provides a useful tool for different actors in the quality assurance system. Its systematic discussion every year is the most common way to warrant CoAl at programme level. This is the first step of the annual quality assurance cycle and the revision of the OER, and follows the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle.

- PLAN: Establish the objectives and processes necessary to deliver results in the upcoming future period.

- DO: Implement the plan and execute the planned processes. Collect data for charting and analysis in the following ‘check’ and ‘act’ steps.

- STUDY: Study the actual results (measured and collected in the ‘Do’ step) and compare against the expected results (targets or goals from the ‘plan’) to ascertain any differences. Look for deviation(s?) in implementation from the plan and also look for the appropriateness and completeness of the plan to enable the execution.

- ACT – If the ‘check’ shows that the ‘plan’ that was implemented in ‘do’ is an improvement to the prior standard, then that becomes the new standard for how the organisation should ‘act’ going forward.

The internal audit meeting

The main output of the audit panel is its report. The audit panel decides for each programme objective whether it has been achieved, based on the information that has been provided. To help structure the discussion (and the report) there is a format which is similar for all AoL audits. This format has several items:

- Introduction: briefly introduces the principles of the AoL system, its purpose, describes the working process of the audit panel, limitations, a word of thanks to those who have helped make the audit happen.

- Validity of the data: touches upon whether the collected information provided the panel with evidence of how well the students have acquired the respective programme objectives.

- List of ILOs: the audit panel discusses per programme-level intended learning outcome whether it has been achieved by the students. In other words, is there constructive alignment? This is the main part of the meeting and the report.

- General conclusions and recommendations: summarizes the conclusions and lists the recommendations to make sure the feedback is communicated in a clear manner to the programme coordinator.

- Feedback on audit process: tips to improve the internal audit process for next time

Please note that the format can change based on new insights or changing needs.

Information management of internal audits

The key to successful internal audits is having access to relevant information sources.

- Assessment programme / Curriculum map:

This document shows the link between the programme-level ILOs and assessment throughout the programme (including the courses, skills, projects or thesis). The assessment is the ‘point of measurement’ to see whether students are on track with regard to the ILOs. - Course manuals

Course manuals provide important contextual information about the courses and their place in the programme - Grade overviews

In most cases, it is interesting to see what the grading is for each type of assessment in the programme. The numbers can be used to start asking questions. For example, if the audit panel sees that a high percentage of students underperform with regard to a certain ILOs, as this can be a signal that something’s wrong. - Assessment

The assessments (e.g. exam questions or assignments) as well as samples of student work are collected. The audit panel uses this to see whether the assessment measures student performance on the ILOs, as stated in the curriculum map or assessment programme. The BSc/MSc Thesis can also be a point of measurement. - Rankings and surveys

There can be signals from rankings and surveys (i.e. indirect measurement) which can help the audit panel focus on certain areas of interest.

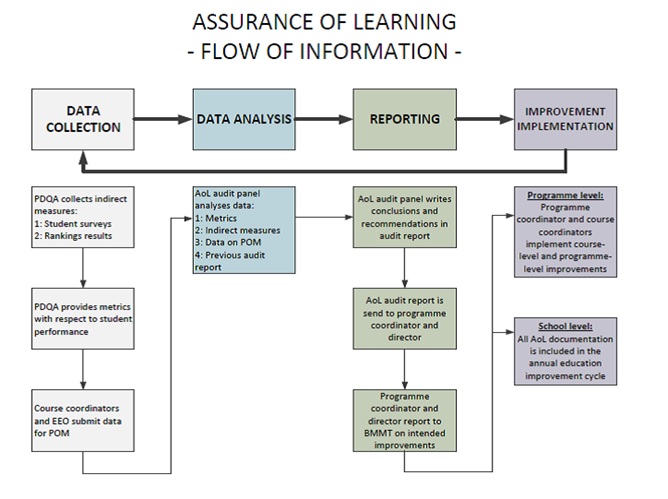

The figure below explains how this information feeds into the audit cycle. First, the information is collected and made accessible by the Policy Development & Quality Assurance Office (PDQA). The audit panel then analyses the data, reports on the findings, and makes recommendations. The programme coordinator and programme director formulate a response in which they state which recommendations they will adopt and implement. Both the report and the implementation plan will be archived as it is the starting point for the next audit cycle. To ensure the report and the reply letter will not be forgotten until the next audit (in three years) they are also input for the annual Education & Examination Regulations (EER) cycle. This has as an additional benefit that the Programme Committee and Board of Examiners are informed as well.

Actors in the internal audit process

An internal audit system like SBE’s Assurance of Learning (AoL) requires different actors to fulfil specific roles. When implementing such a system it is wise to map the roles and responsibilities of different actors, depending on the organisational culture and institutional context. At SBE the following actors are involved:

- Audit panel: small group of peers (academic staff), when available, includes an alumnus or a contact from future professional environment of graduates. The panel reviews the degree of constructive alignment in an education programme.

- Programme coordinator: Is the main contact for the audit panel, and speaks on behalf of the curriculum team (course coordinators).

- Programme coordinator (II): (also called programme director/ director of studies in faculties): is responsible for starting and finishing audit processes, thereby keeping close contact with programme coordinators.

- Course coordinators: discuss proposals and implement improvements.

- AoL coordinator: facilitates the audit process in terms of planning and communication, and instructs the audit panels.

- Education & Exams Office: collects data concerning assessment.

- Programme Committee: receive all audit reports in the context of the annual EER cycle.

- Board of Examiners: receive all audit reports in the context of the annual EER cycle.

- SBE Board: receives all audit reports in the context of the annual EER cycle.

It is recommended to experiment before implementing a full scale AoL system, for example by doing a pilot with one or two education programmes. These early adopters should accept that things can be a bit messy, and can act as ambassadors when upscaling the operation.

Implementation and transparency

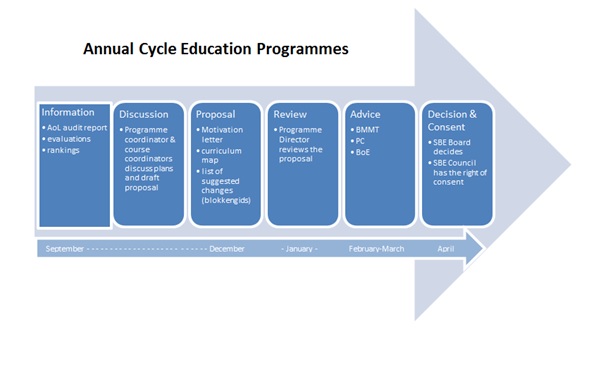

It is very important that the actors involved who dedicate time and energy in the audits perceive the process as being effective and result-oriented. One way to achieve this is to make sure the audits are embedded in the annual EER cycle. This ensures that all stakeholders are reminded of the improvements exactly at the moment when the changes for next year’s education programme are being discussed and decided upon. This is a helpful reminder for programme and course coordinators and simultaneously makes transparent for advising and deciding bodies (a) what the specific improvements are which will be implemented and (b) that there are structural and well-documented mechanisms to reflect on the curriculum.

Azer S, McLean M, Hirotaka O, Masami T & Scherpbier, A (2013) Cracks in problem-based learning: What is your action plan? Medical Teacher, 35(10): 806-814.

Dolmans DH, De Grave W, Wolfhagen IH, van der Vleuten CP (2005) Problem-based learning: future challenges for educational practice and research. Medical Education, 39(7):732-741.

Moust J, van Berkel H, Schmidt (2005) Signs of erosion: Reflections on three decades of problem-based learning at Maastricht University. Higher Education 50: 665–683.